4.20.2025 -A Lesson in Financial Shenanigans, Tax Arbitrage, and Dividend Loops in Brazil

Understanding the interplay of tax structures, corporate governance, and financial reporting in a jurisdiction where the footnotes matter more than the headlines.

Every week, I’ll share insights on what I’m seeing in the market and provide data on LatAm tech. Follow to stay updated on the latest trends and share to support.

These past weeks brought a series of interesting events. I had the chance to speak on a panel at the South Summit, where I shared ideas on LatAm growth investing alongside Carlos Pessoas, Managing Director at G2D, and Ralph Malzoni, founder of Neofeed. Both are individuals I deeply admire, with remarkable careers, and we had engaging discussions on the future of growth investing in the region. The South Summit team did an excellent job curating an audience of founders, investors, and ecosystem stakeholders from across the globe. The event was well-organized from start to finish. If you get the chance, I highly recommend attending as it’s a great way to deepen your understanding of the LatAm ecosystem.

On a more personal note, I also ran a half-marathon in São Paulo, finishing with my third-best time despite limited training. My pace was 5:06/km—not outstanding, but solid. Running has become one of my core passions over the past year. It’s a discipline-builder: waking up early forces you to sleep early, which in turn sharpens your daily schedule and boosts productivity.

Financial Shenaningans: Dividends, Corporate Structure, and Tax incentives

In this edition, I want to explore a nuance of a financial structure, or as I like to define, financial shenanigan, uniquely existent and created by the Brazilian tax system and its incentives.

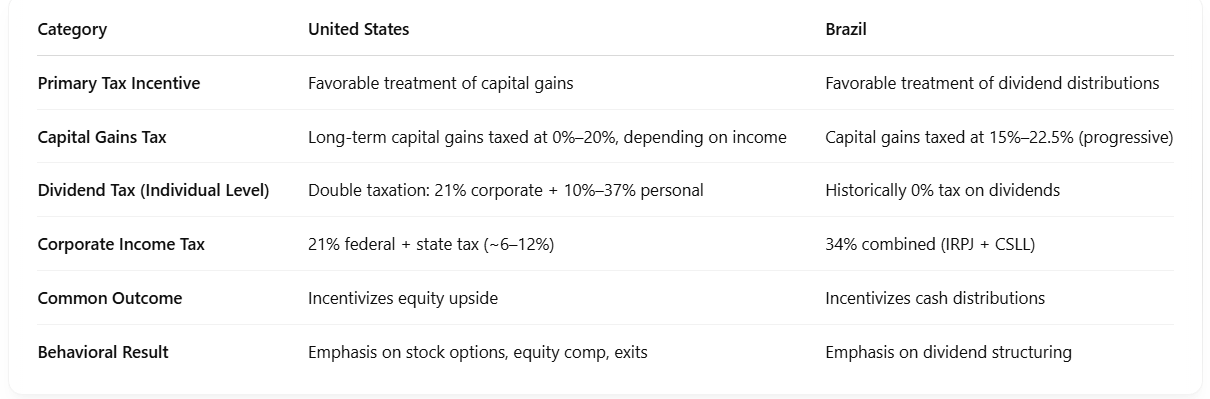

Whereas the United States tax system provides the strongest incentives for income to be distributed via capital gains as a result of marginal tax rates on capital gains being lower than those on income, in Brazil, dividend distributions are taxed at 0%, while both capital gains and income are taxed at significantly higher rates starting at 15% and increasing incrementally to 27.5%.

This asymmetry incentivizes companies to engineer structures that maximize dividend distributions in order to reduce their tax burden. As a sweetener, it also enables them to inflate financial performance by reclassifying expenses from the income statement as dividends—effectively distributing cash off the books and inflating EBITDA. The result is often a lower effective tax rate that can mislead investors unfamiliar with local tax regulations and attract scrutiny from tax authorities, as it circumvents key elements of the formal tax system.

As Charlie Munger often emphasized, incentives are among the most powerful forces shaping human behavior. Unsurprisingly, business strategy tends to follow them.

How I learned about this insight came from one of the first transactions I was deeply involved in during my time in venture capital in Brazil. It was a minority investment opportunity in a company that operated in the financial services industry. The deal ultimately didn’t go through, but it left me with a valuable lesson that didn’t require living with the consequences of the mistake.

The opportunity came to us almost a decade ago. On paper, it had all the characteristics we looked for in companies disrupting traditional services through technology. The business operated in a niche segment of Brazil’s regulated financial economy and reported a margin surplus of 10–15% above its peers. It benefited from regulatory tailwinds, driven by Central Bank reforms, and a favorable monetary environment. Growth was strong.

Management presented a sophisticated architecture of technological infrastructure. Their pitch was clear: they could deliver services more efficiently with fewer employees. The promise of tech-enabled efficiency was compelling—this was before large language models went mainstream, and similar businesses in the U.S. were performing exceptionally well.

We built conviction quickly. The company served a niche customer profile with high retention, recurring revenue, and a cash flow profile that supported EBITDA margins well above industry benchmarks—even exceeding some mature software firms. The team emphasized automation, scalability, and operational leverage. Their dashboards showcasing product usage were thoughtful, well-designed, and pointed to a differentiated value proposition.

We bought into the narrative: that technology and automation had enabled the company to reduce headcount, boost margins, and drive profitability. But as we dug deeper, the real story was not about software—it was about structure.

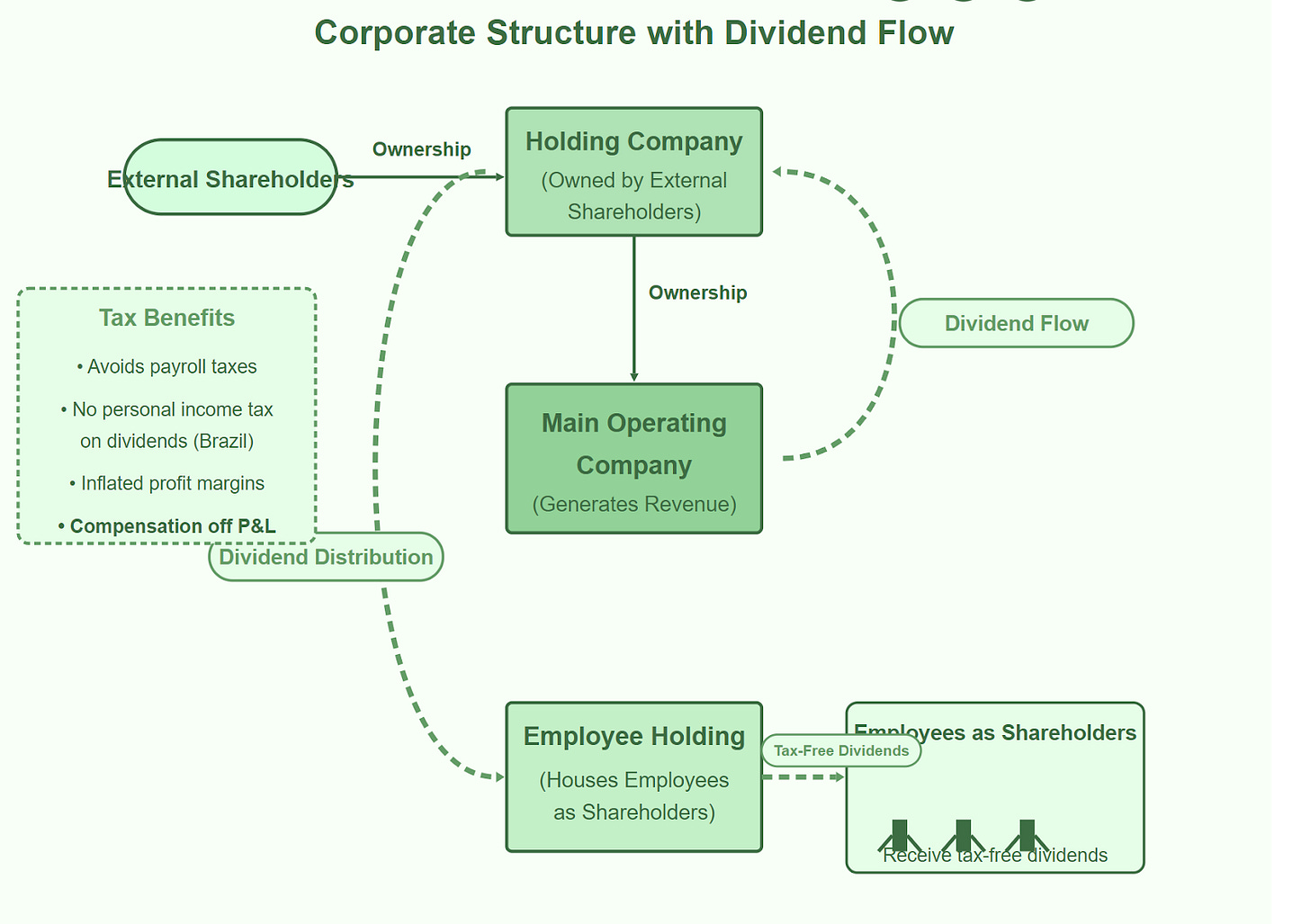

The company had implemented a mechanism through which a significant portion of salaries and general expenses were routed outside the income statement. Employees became shareholders in a holding company that received dividends from the operating entity. Those dividends were then redistributed to the employees as compensation. Since these payments didn’t pass through the P&L, they were not recorded as operating expenses.

In effect, the company was funneling profits to a holding entity, which in turn paid employees. To an outside investor, the financial statements suggested superior margins. In reality, those margins were artificially inflated. The true economic profile of the business was in line with industry norms. the margin excess was a mirage enabled by tax and financial engineering.

The Broader Lesson: Tax Systems Create Incentive Structures

One of the first things I learned returning to Brazil from the U.S. is how dramatically tax regimes shape business behavior. Brazil's 0% tax rate on dividends drives very different optimization strategies.

Implication #1: Founders Optimize for Different Outcomes

In the U.S., founders optimize for capital appreciation—IPOs, M&A, or VC exits—because capital gains are taxed favorably.

In Brazil, the incentive flips. Founders often optimize for near-term cash extraction via dividends and off-balance-sheet structures.

This opens the door for aggressive financial engineering that creates the illusion of performance.

Implication #2: Brazilian Corporate Law Enables Disproportionate Dividends

Under Brazilian corporate law (Law No. 6.404/76, the Lei das S.A.), companies must distribute at least 25% of net income as dividends unless otherwise specified in the bylaws. Normally, dividends must be distributed proportionally to shareholder ownership. However, the law allows the creation of different share classes with distinct economic rights—for example, preferred shares with fixed or priority dividends.

To legally enable disproportionate dividends, companies must outline these mechanisms clearly in their bylaws and, where necessary, reinforce them in a shareholders' agreement. Any deviations from proportionality must not infringe shareholder rights under the principle of interesse social (corporate interest) and must be approved in shareholder meetings.

These structures create flexibility to reward active founders or incentivize performance while remaining compliant—provided the setup is transparent, consensual, and legally sound.

In short, a shareholder can receive a disproportionately larger share of the economic upside without owning an equivalent equity stake, enabling profit distributions without diluting equity.

This enables a company to have a shareholder have greater share of distributions than the actual ownership in the company, therefore enabling payouts without subsidizng the equity

Implication #3: These Structures Create Serious Risk

While these setups offer short-term tax and optical advantages, they come with significant downsides for institutional investors:

Labor Risk: Regulators may reclassify dividend payments as disguised salaries, triggering retroactive fines and social security obligations.

Tax Liability: Structures designed to minimize taxes can backfire during audits or M&A events.

Governance Risk: They reduce transparency, complicate P&L visibility, and distort performance metrics.

How the Structure Actually works in a Diagram

In the example I encountered, G&A expenses were effectively offloaded to a separate entity. The employee holding company received dividends from the operating entity and redistributed them to employees as compensation. These costs were incurred outside the company’s financials, allowing the firm to report artificially high margins.

At the same time, it allowed employees, that had become partners of the holding company to have increased compensation by bypasssing taxes - altough having a legal liability - therefore increasing their bottomline.

This structure misrepresented the company’s financial health. And I now view this pattern as a critical risk factor to investigate during diligence and part of a checklist of analysis whenever a company is profitble and distributing dividends.

If you are an Investor, Operator or Corporation it is relevant to understand this structure as a means to protect yourself.

The impact of the structure to consider when evaluating such case:

Earnings Quality Risk: The exclusion of executive compensation and related personal expenses from the operating company’s P&L may lead to an overstatement of core profitability. While this structure may enhance reported EBITDA margins in the near term, it reduces transparency and comparability versus peers, and may inflate valuation multiples on a misleading basis.

Tax Optimization vs. Deferred Liabilities: Structuring executive compensation to minimize personal income tax burdens can be tax-efficient in the short run. However, it introduces material tail risks across tax, labor, and governance domains. Should regulatory authorities recharacterize such flows as employment income or dividends, the company and its executives may face retroactive liabilities.

Governance and Control Complexity: When operating subsidiaries house minority shareholders outside the main cap table, parent-level control is diluted on the holding level.

LatAm Tech Markets Update: The Rollercoaster continues, Tariffs Pause and Brazil is a winner

In times of global trade uncertainty like the ones we face today, Brazil holds a distinct advantage as a major global supplier of commodities and food, supported by a flexible and adaptive governance model. The country maintains trade relationships with China, the United States, the GCC, and Europe not only for economic gain but also out of societal necessity. Our role as a provider of essential goods, combined with a non-militaristic stance toward other economies, has positioned Brazil to benefit meaningfully from this evolving landscape of globalization, deglobalization, or whatever one chooses to call it.

In this context, I’ve been speaking with colleagues and experts who are optimistic—not because they expect exceptional short-term outcomes, but because they believe Brazil is structurally well-positioned, regardless of how the geopolitical dynamics unfold.

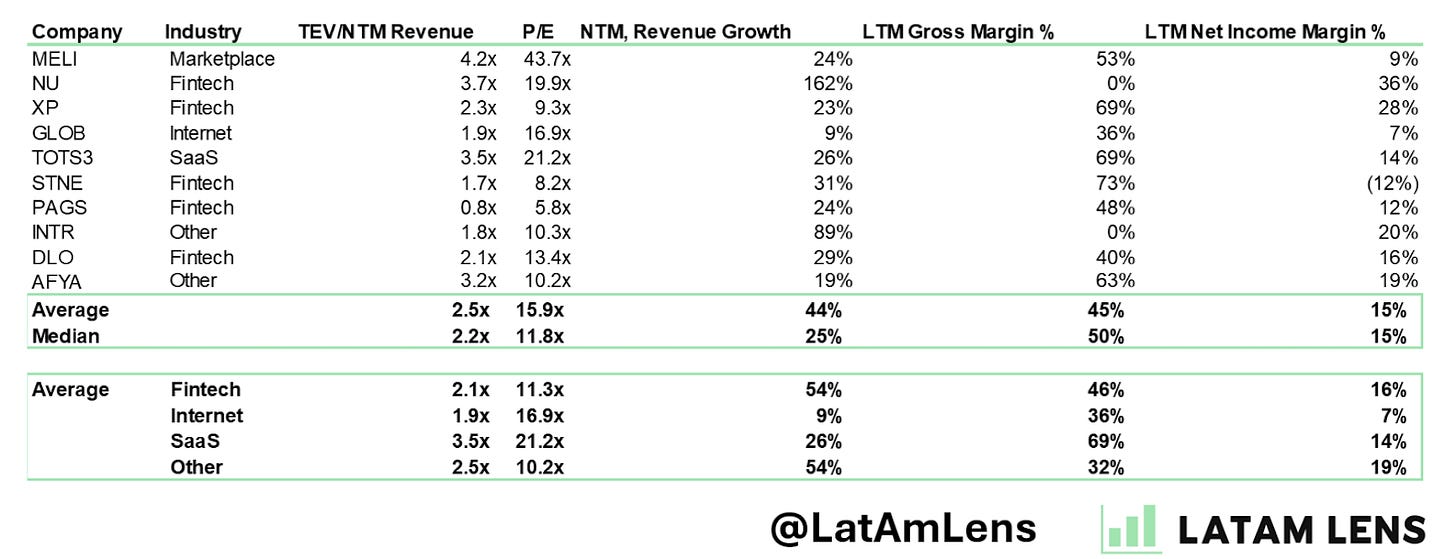

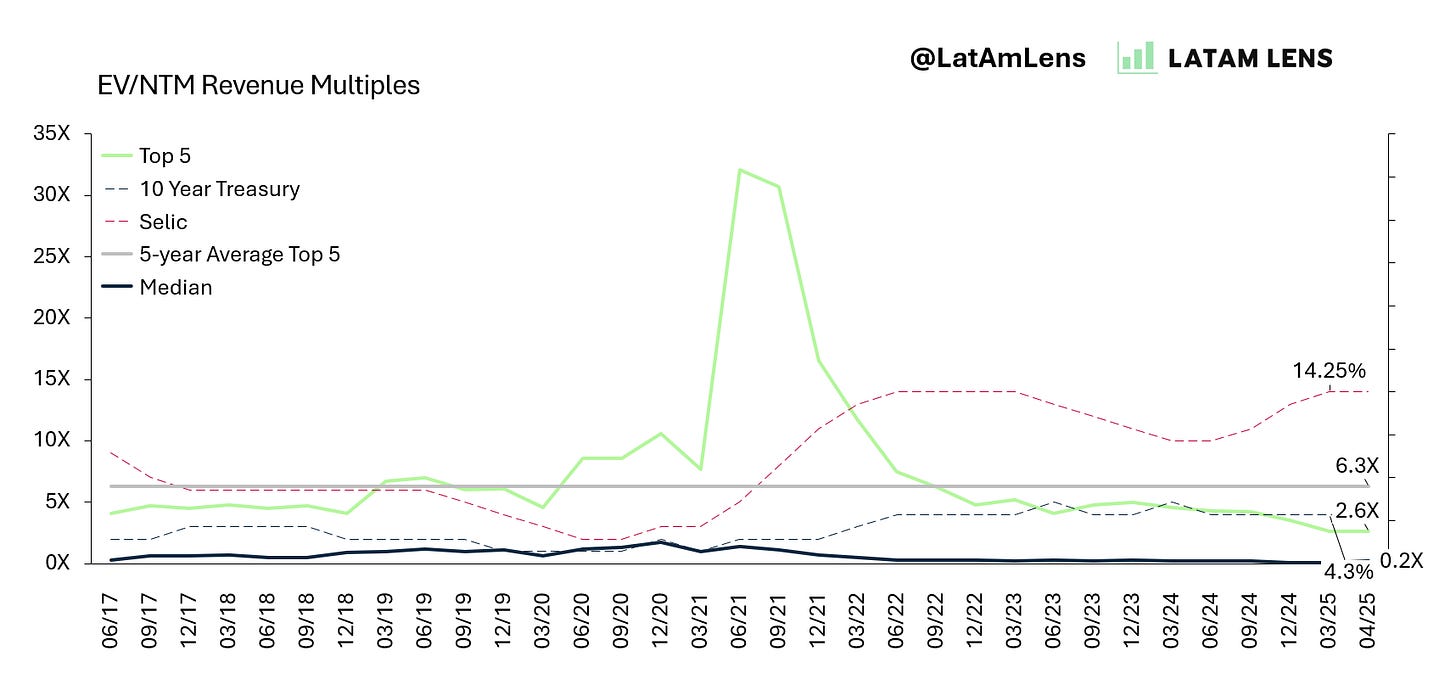

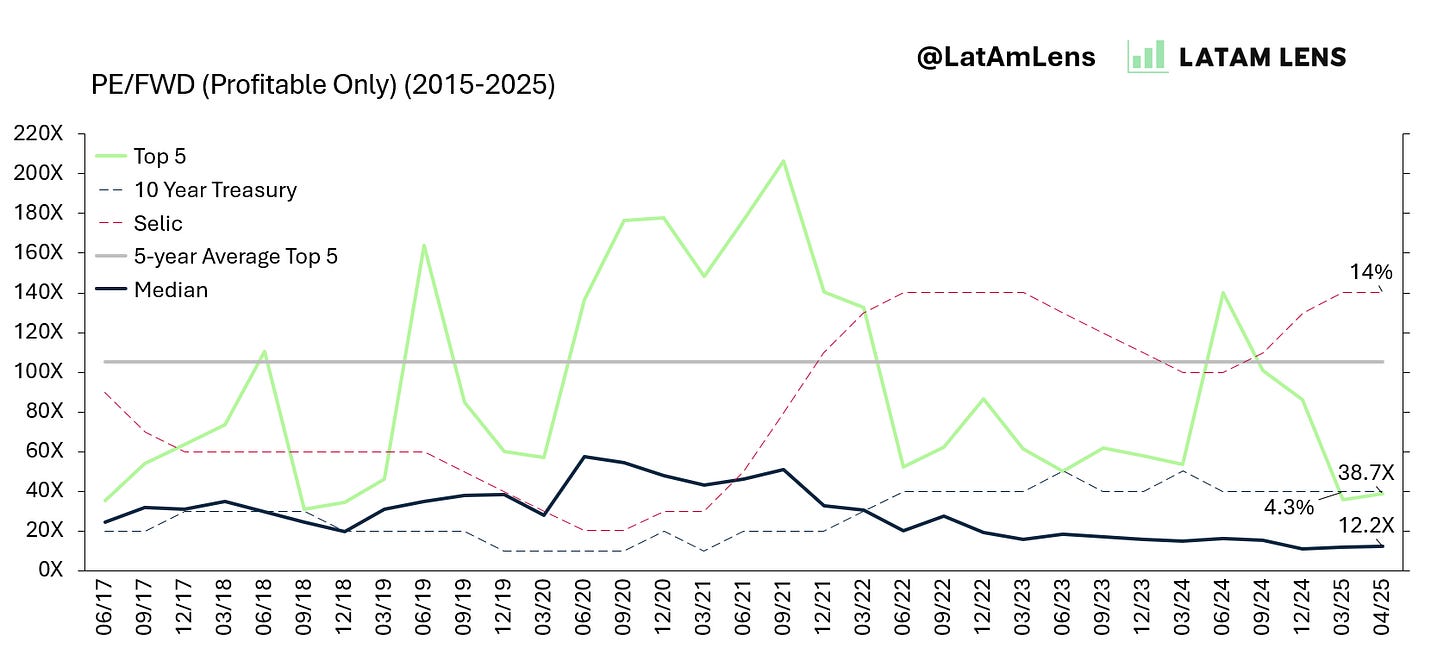

Interestingly, public market sentiment has also started to recover. The median EV/Forward Earnings multiple for the top five tech companies by market cap in Latin America has risen from 35.7x to 38.7x since the start of the quarter. At the same time, EV/Revenue multiples have climbed from 2.4x to 2.6x across the same group, reflecting a broader bounce in market confidence.

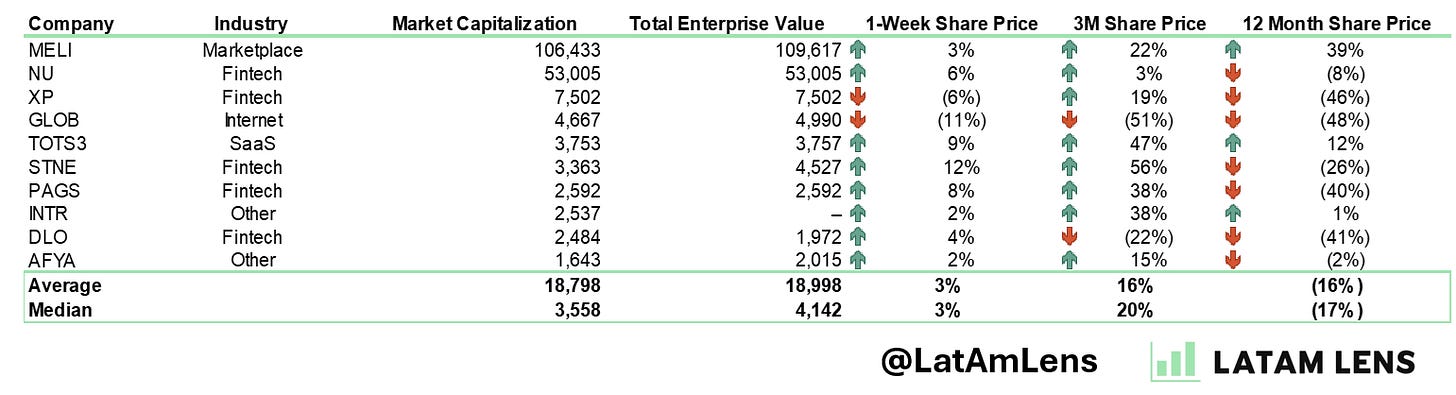

LatAm Top 10 Companies by Market Cap

LatAm Top 10 Tech Companies Weekly Share Movement

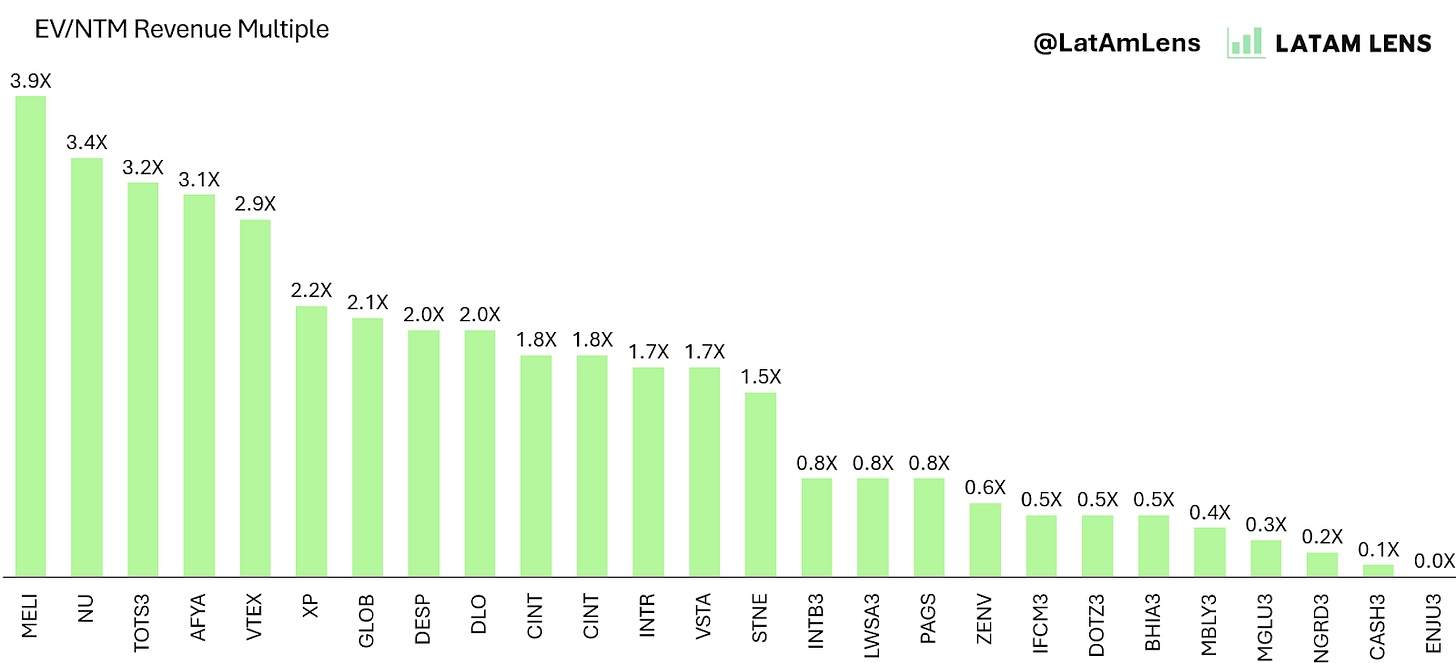

EV/NTM Revenue Multiple

EV/NTM Revenue Multiple (2017-2025)

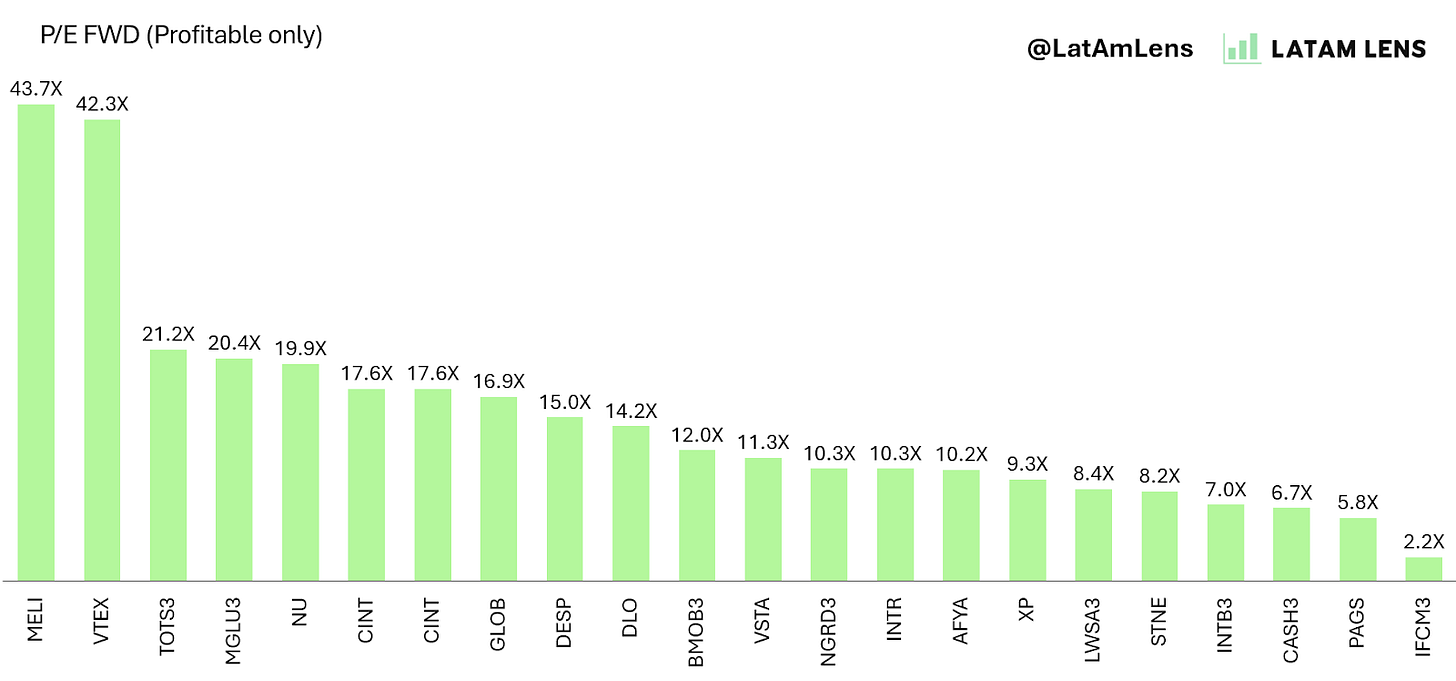

PE/FWD (Profitable Only)

PE/FWD (Profitable Only) (2015-2025)

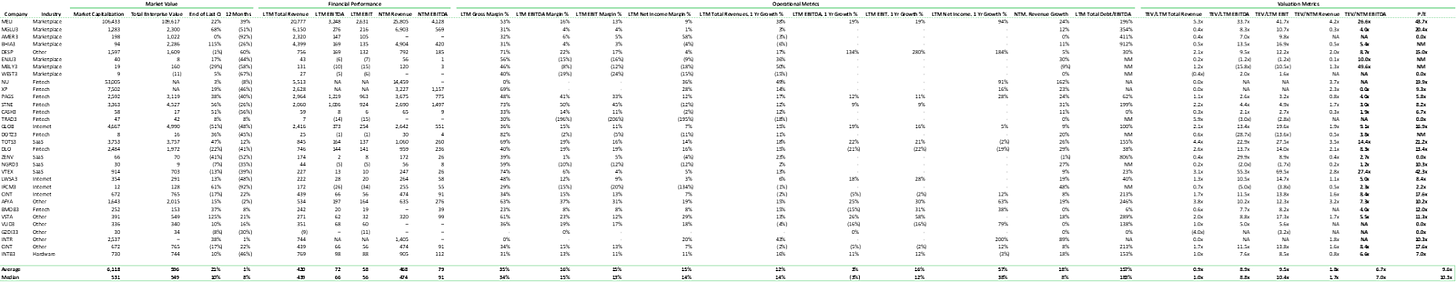

Comp Set

Sources used in this post include CapitalIQ, CB Insights, and company filings. Source data is from 4/17/2025.

The information presented in this newsletter is the opinion of the author and does not necessarily reflect the view of any other person or entity, including Upload Ventures. The information provided is believed to be from reliable sources but no liability is accepted for any inaccuracies.